What No One Told Me About Becoming a Different Version of Myself

I believed in science with my whole being.

I believed in medicine, in skilled hands, in protocols and knowledge and sterile rooms that smelled like safety. I believed that when you entrust your life to a neurosurgeon, you are carried – held inside a system built on precision.

And yet on the morning of my AVM embolization, my body betrayed the story my mind insisted on. I was trembling. Not from cold.

From something deeper – a primal, intuitive fear I couldn’t rationalize away.

I’d always treated hospital stays almost like a forced retreat: a strange rest from the noise of daily responsibilities. I’d never feared procedures, needles, scars, or even general anesthesia. Pain was familiar, and uncertainty didn’t scare me.

But that morning was different.

The night before, I had written goodbye letters to my daughter and my husband – pouring everything I loved into those pages, as if words could protect them or keep me alive in their hearts. I told myself it was unnecessary, overly dramatic. The medical team repeated:

“It’s a simple embolization”.

“That vessel doesn’t supply anything essential”.

“It’s safe. Non-invasive”.

“You’ll be home in two days”.

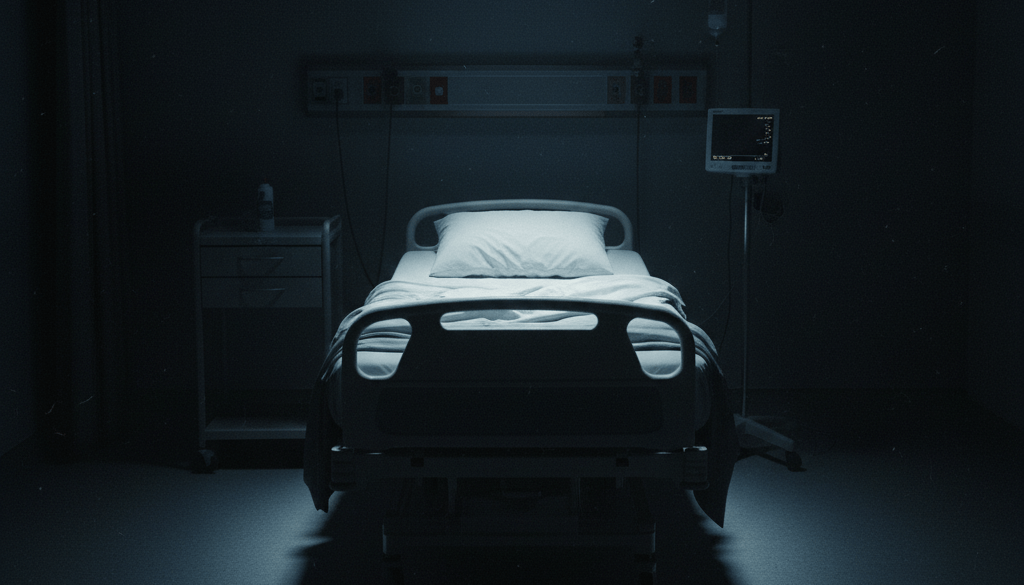

But when they showed me my hospital bed, I looked out the window. Right below it – plainly visible – were the doors of the morgue.

A cold, unmistakable shiver went straight through me. My chest tightened. My breath thinned.

It was as if something inside whispered, “Read the signs. Pay attention”.

Lying on the portable bed outside the surgery room, I felt very small – reduced to something fragile and childlike. My hands wouldn’t stop shaking. My feet were icy under the thin cover. I listened to my own heartbeat thumping irregularly, like it was trying to warn me. Around me, nurses moved with calm efficiency, but inside me the universe felt sharp, hollow, echoing.

I tried to pull myself together.

“They won’t even shave your head”.

“This is routine”.

“Look at the positive side, this AVM time bomb has to be deactivated”.

But fear has its own language, and mine had already begun to speak.

The doors opened.

The surgical team – angels in pale green – smiled at me from behind masks. They guided my rolling bed into an impossibly bright room. The lights above me blurred.

And then I vanished.

When I woke up, I had already become someone else.

The infarction happened during the embolization – a blockage that cut off blood flow to parts of my parietal and temporal lobes. These regions shape so much of what makes us “us”:

- movement and body awareness

- coordination and spatial understanding

- sensory integration

- visual fields

- memory and language pathways

- emotional interpretation

- the sense of “where I am in space, where my body ends, and the world begins”

When blood flow stopped, neurons died.

Pathways dissolved.

Networks went silent.

And so when I opened my eyes, the world didn’t match the version I remembered.

My right side – my arm, my leg, half my face – felt like it wasn’t attached to me.

Hemiplegia.

A quiet, heavy paralysis.

My vision sliced the world in half – right-sided hemianopsia – like someone had erased part of reality with a stroke of black paint. The left half of the room existed, the right half was a void.

My brain throbbed with edema – swelling that made even thinking feel thick and underwater, as if my consciousness was wading through syrup.

And yet, strangely, I was calm.

Not because nothing was wrong, but because everything was too wrong for the brain to fully compute. Confusion wrapped me like plastic film.

“Doctor”, I said softly, politely,

“I can’t feel or move my right side.

I see… differently.

And could you bring me some cocoa and a cookie? I’m starving”.

It sounds impossible – but the brain protects itself in surreal ways. Cognitive shock, steroid haze, and partial disorientation made everything muted, dreamlike.

That was the moment I realized:

I hadn’t just survived something.

I had crossed a threshold.

I was born twice – first in 1987, and again in 2018.

No one tells you that you can wake up from surgery and meet yourself as a stranger.

No one tells you that an infarction can rearrange your identity, your senses, your personality, your way of understanding the world.

No one tells you that recovery is not just physical – it’s existential.

I woke up in a body that didn’t move the way I remembered, with senses that didn’t align, with a brain that processed light and sound and space through a different map.

And yet, against all odds, I lived.

And I became a different version of myself – one I still learn, every day, to recognize, understand, and appreciate.

A quieter version.

A stronger version.

A version shaped by both science and survival.

A version born from the light of an operating room, from loss, and from an unplanned second chance.

By Nataliya Popova

Mindly Different – Coaching for the beautifully different mind

Leave a comment