The Psychological Cost of Masking

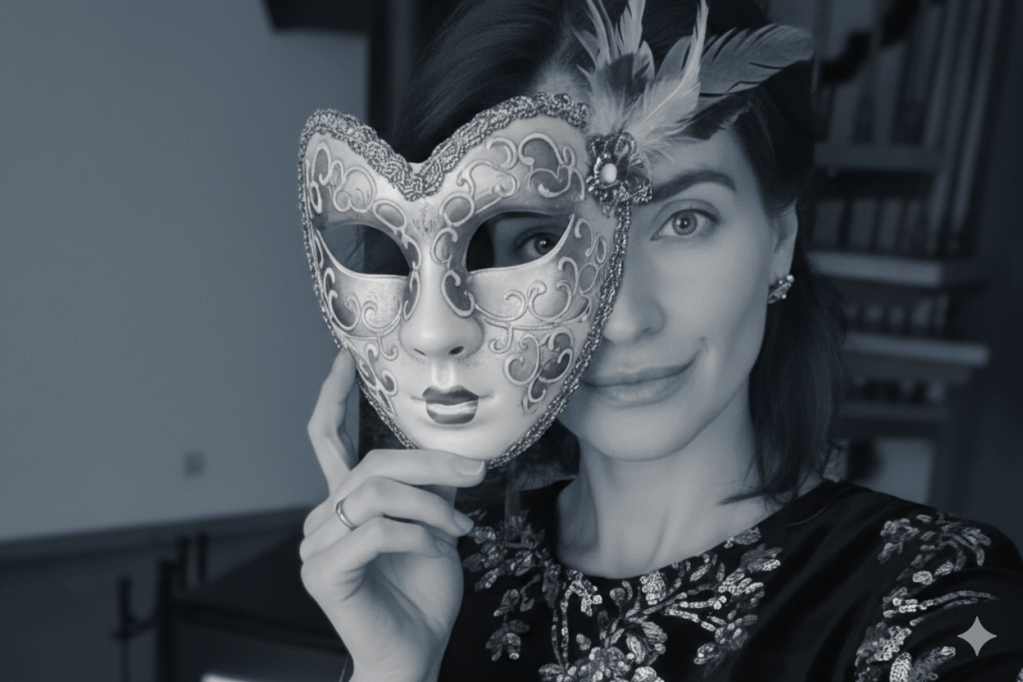

There is a performance many neurodivergent people give every day.

Not on a stage. Not for applause. In classrooms, workplaces, family gatherings, and social spaces.

It involves studying others’ facial expressions and mirroring them. Scripting conversations in advance. Forcing eye contact even when it feels painful. Suppressing the urge to move, stim, or simply withdraw. Monitoring every word, gesture, and reaction to ensure nothing “strange” slips through.

This performance is called masking – and it comes at an extraordinary psychological and physiological cost.

If you have ever felt like you are living two lives – one authentic, one performed – this is not weakness or deception. Masking is the process of intentionally (or unintentionally), hiding aspects of yourself to avoid harm. It is a survival strategy developed in response to a world that does not always accommodate different ways of being.

But survival strategies, when sustained over years, exact a steep price.

This post builds on the neurobiological foundations explored in Masking and the Brain, moving from what happens inside the nervous system to how long-term masking quietly shapes a person’s inner life.

What Is Masking?

Masking is most commonly discussed in the context of autism and ADHD conditions, but it occurs across the neurodivergent spectrum – and even among neurotypical people navigating stigma or social pressure.

At its core, masking involves suppressing or camouflaging natural behaviors to fit neurotypical social norms.

This might look like:

- Forcing yourself to make eye contact even when it feels overwhelming or unpleasant

- Scripting social interactions in advance and rehearsing responses (and getting anxious about it!)

- Suppressing stimming behaviors (hand-flapping, rocking, fidgeting)

- Mimicking others’ body language, tone, and expressions

- Hiding sensory sensitivities (enduring loud environments, bright lights, uncomfortable textures)

- Forcing enthusiasm or interest when you feel exhausted

- Monitoring your every word and gesture to avoid seeming “weird”

Masking could make neurodivergent employees appear “professional” or “easy to work with” on the surface. But it is not a sign of thriving.

It is not easy to breathe under the mask. Masking is a high-cost survival strategy, but for many, it is not a conscious choice. It begins in childhood, when neurodivergent children receive clear messages – through peers, teachers, or media – that their natural behaviors are wrong, “weird” or unacceptable. To cope, they adapt by hiding their differences.

Over time, masking becomes automatic.

You may not even realize you are doing it.

The Psychological Theory Behind Masking’s Toll

Self-Determination Theory: The Undermining of Basic Needs

One of the most powerful frameworks for understanding masking’s psychological cost is Self-DeterminationTheory (SDT), developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan.

SDT proposes that all humans have three fundamental psychological needs:

- Autonomy – the need to feel that your actions are self-directed and aligned with your authentic self

- Competence – the need to feel effective and capable

- Relatedness – the need to feel connected to and accepted by others

When these needs are optimally supported, evidence suggests that people are more autonomous in their behaviors, are more likely to persist at their behaviors, and feel better overall.

But masking systematically undermines all three needs.

Autonomy is violated because your behavior is not self-directed – it is controlled by external pressure and the need to avoid judgment. You are not acting from your own values or preferences. You are performing what you believe others expect.

Competence becomes hollow because when success is attributed to one’s ability to “pass” as neurotypical, rather than to one’s genuine skill or effort, the resulting sense of achievement may feel hollow or disconnected. You cannot trust your accomplishments.

Did you succeed because you are capable, or because you successfully hid who you are? That is a scary question to ask yourself.

Relatedness is compromised because masking may yield polite, socially acceptable, but surface-level interactions that leave neurodivergent individuals feeling unseen or misunderstood, especially if acceptance and relatedness are contingent on continued performance of an inauthentic or false self. You are connected to others – but not as yourself. The connection is conditional on maintaining the mask.

When these three fundamental needs are not met – or actively frustrated – our psychological well-being deteriorates.

Prolonged periods of being externally regulated can lead to enduring decreases in well‐being. People may eventually switch to a controlled mode of self‐regulation, in which their strivings become disconnected from their true psychological needs.

This is not abstract theory. This is what happens when we spend years, or decades, hiding ourselves.

The Emotional and Identity Consequences

Chronic Exhaustion and Burnout

Studies have linked masking to an increased risk of burnout, depression, anxiety, and identity erosion. The chronic stress of constantly monitoring behavior, scripting social interactions, and second-guessing oneself can be mentally and emotionally draining.

This is not ordinary tiredness. It is depletion at a neurological level.

Every moment spent masking requires cognitive resources. You are running two parallel processes:

what you naturally want to do, and what you are forcing yourself to do instead. This creates sustained cognitive load.

The brain cannot sustain this indefinitely. Eventually, it reaches a breaking point. This is often called

autistic burnout or neurodivergent burnout – a state of extreme mental, emotional, and physical exhaustion specific to the demands of masking and navigating a neurotypical world.

Loss of Identity

One of the most devastating consequences of masking is the loss of authenticity. Many neurodivergent individuals report feeling as though they are living a double life – one where they must constantly suppress their true selves to be accepted by others.

When you spend years performing a version of yourself, the line between performance and reality blurs.

You may lose touch with:

- What you genuinely enjoy vs. what you think you should enjoy

- How you naturally express emotion vs. how you have learned to perform it

- What your authentic voice sounds like

- Who you are when no one is watching

Personally, after the brain injury I recognized that I didn’t know what my “true personality” was. However, despite knowing that I felt like I was “acting” in many situations and would change my personality to fit the people around me, I did not know the price my nervous system and my “self” was going to pay for that.

This dissociation from self is not a minor inconvenience.

It is a fracturing of identity.

Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation

This dissonance between internal reality and external presentation can lead to feelings of isolation, self-doubt, and even suicidal ideation in severe cases.

When you cannot be yourself anywhere – when every social interaction requires monitoring, control, and suppression the world becomes an exhausting and lonely place.

You are surrounded by people, but fundamentally alone. Because no one sees you. They see the mask.

Research and clinical observation link chronic masking with heightened anxiety, identity confusion, feeling emotionally drained, and dissociation. Anxiety becomes chronic because you are always on alert – scanning for social cues, anticipating judgment, adjusting your behavior in real time. There is no rest.

Depression emerges from the profound sense of disconnection – from others, from yourself, from any sense of authentic belonging.

The Physiological Cost: What Masking Does to the Body

Masking is not only psychological.

It is physiological.

The HPA Axis and Chronic Stress

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body’s central stress response system. When you experience stress, the HPA axis activates, releasing cortisol – the primary stress hormone.

Cortisol is essential for life. In acute situations, it helps you respond to threats. But chronic elevation of cortisol the kind that comes from sustained masking – has devastating effects.

Research shows that neurodivergent individuals, particularly autistic people, often have elevated baseline cortisol levels. Cortisol levels are much higher in people with autism and the severity of a child’s autism may be directly linked with the level of stress or anxiety they experience on a day-to-day basis.

When you add masking to already elevated stress levels, the HPA axis becomes dysregulated, what can result in dysregulated stress response phenotypes that demand a physiological cost that is referred to as allostatic load.

As we saws in previous posts, allostatic load is the cumulative wear and tear on the body from chronic stress.

It affects:

- Immune function – chronic stress suppresses immune response, making you more vulnerable to illness

- Cognitive function – elevated cortisol impairs memory, attention, and executive function

- Sleep regulation – cortisol disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to insomnia or poor-quality sleep

- Metabolic function – chronic stress affects blood sugar regulation and increases inflammation

Stress of burnout can overwhelm cognitive function and the neuroendocrine system, which leads to physical changes in the anatomy and functioning of the brain.

Stress and anxiety lead to an increase in cortisol and adrenaline, and their long-term or chronic existence in the body can ultimately alter neural pathways.

This is not metaphorical. Masking changes your brain.

Why Do People Mask?

If masking is so costly, why do people do it?

Because the cost of not masking often feels higher. Masking is often driven by stigma avoidance.

People mask because:

- They fear judgment, bullying, or social rejection

- They worry about career consequences or being perceived as “not promotable” or “not hirable”

- They lack accommodations or understanding in their environments

- They have been explicitly (or implicitly) told their natural behaviors are wrong

Masking is not a free choice.

It is a response to a world that demands conformity.

And for many people masking becomes so deeply ingrained that unmasking feels impossible or terrifying.

Reducing the Need to Mask

The solution is not to tell neurodivergent people to “stop masking.” That places the burden on individuals to bebraver, more authentic, more resilient.

The solution is to change the environments that make masking necessary.

At the Systemic Level:

- Workplaces and schools must become genuinely inclusive, not just accommodating on paper

- Sensory-friendly environments should be standard, not special requests

- Evaluation should focus on outcomes, not personality or conformity to neurotypical social norms

- Flexibility should be normalized – remote work, flexible hours, quiet spaces, reduced meeting demands

At the Individual Level:

- Recognize that masking is not your fault. You developed it to survive.

- Allow time to recover after social interactions that require masking

- Use frameworks like “energy accounting” or “spoon theory” to understand what drains and recharges you

- Seek neurodivergent community – spaces where you do not have to mask

- Work with affirming therapists who understand masking and do not pathologize neurodivergence

For neurodivergent individuals, therapy can become a safe space to be themselves. Unmasking doesn’t happen all at once. It shifts depending on the environment and how safe a person feels.

Unmasking is not a single decision.

It is a gradual process of finding spaces – and people – where you can breathe.

Masking Is Not Strength. Authenticity Is.

For too long, the ability to mask has been mistaken for resilience or high functioning. But masking is not a sign of doing well.

It is a sign of adapting to environments that do not accept you as you are. The goal is not to become better at masking. The goal is to create a world where masking is no longer necessary.

You are not broken for needing to mask.

You are not weak for being exhausted by it.

You are human, trying to exist in a world that was not designed for you.

And that world needs to change – not you.

By Nataliya Popova

Mindly Different – Coaching for the beautifully different mind

Leave a comment